Inspired by nature: Phil’s story

-

Date posted: 19/11/2020

-

Time to read: 10 minutes

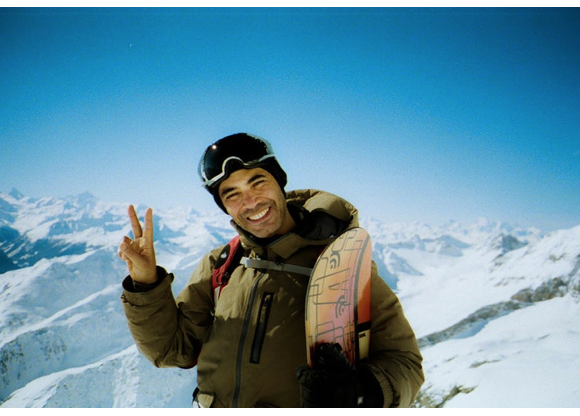

Phil Young

Marketing company boss Phil Young, self-confessed middle aged ‘shredder’, lives in south London and is one of the founder members of Black Trail Runners. He took up this pursuit like he’s taken up every other; from surfing to snowboarding, riding to cycling, because he was inspired to get outdoors at a very young age. Unfortunately, he argues, his experience is still too rare for people of colour.

‘As a child growing up in a predominantly white area, you’d get name calling more or less every day,’ Phil recalls.

In the 1980s, unfortunately, it wasn’t a particularly uncommon experience for many people of colour but Phil’s response certainly was uncommon. ‘Getting on my bike and riding into the countryside was a great way of getting away from it all,’ he says. ‘Being able to cycle out gave me a sense of freedom.’

Phil would cycle from his childhood home in the borough of Enfield to immerse himself in the woodlands of Potters Bar, the marshes of Cheshunt and the other green spaces nearby but his enduring relationship with the outdoors actually started on a humble wasteland.

‘I think it was a former bomb site and we kids would play on it; climbing trees, noticing the plants and the birds, that kind of thing,’ he says. ‘I wouldn’t call it an escape particularly, but it did give me the essence of being part of the natural world and I liked that.’

‘In nature you feel part of something much bigger. Being outdoors you get real weather and a sense of being properly alive. I like the fact that there’s rain on my face, I like the fact that I’m slightly uncomfortable whilst traversing these landscapes; I’m out of my comfort zone. Outdoors you’re part of this eco system that you’re travelling through; that you don’t really get when you live in a city.’

His love of the outdoors was sparked by his inspirational grandfather, Bob. ‘I was brought up by my mother and Bob, who was my father figure and still is my hero,’ he says. ‘He told me very early on: “If you want it, you need to go and get it, it’s all out there” and he was right.’

Bob took Phil travelling and encouraged him to enjoy almost every outdoor pursuit available; from camping in the wilds of Scotland, to riding, surfing and skiing – a sport that enabled him to discover snowboarding. As he grew older, Phil took up mountain biking and trail running.

Earlier this summer he and a group of fellow enthusiasts started Black Trail Runners for the simple reason that, even in 21st century Britain, seeing people of colour camping, hiking, enjoying the National Parks and, of course, trail running, is relatively rare.

The reasons, he believes, are historic. ‘If you are Black in the UK there’s a chance you are here because of the Windrush Generation; people from British colonies who were asked to come and help re-build the country after World War II.’

He says Afro-Caribbean people ended up living in the inner-city by default because from their arrival they were denied the opportunities and work afforded to their white counterparts, yet most of them would have previously lived rurally, in the countryside of the Caribbean islands.

The vast majority of their descendants are now rooted in cities. ‘We’ve lost that generational connection with the environment,’ he says. ‘You go to Jamaica and it’s all outdoors; the Caribbean is outdoors. We are outdoor people but we’ve been urbanised and forced to live in cities.’

He believes this has directly lead to minority communities not always knowing they are ‘part of the story’ of the outdoors. ‘Where I grew up, the experiences I had gave me the tools to navigate it, both socially and environmentally,’ he says. ‘But for others in those landscapes, if you don’t feel as though you’re wanted or needed or have any heritage in those places, there’s this sense of “is this my space, should I even be here?”

Changing this is vital and practical because, ‘If you don’t have an emotional engagement with the real outdoors, the wild outdoors, how can you be expected to give a damn about the environment?’

Black Trail Runners and the Black Cyclists Network, which he’s also a part of, are helping tackle the issue of black visibility in the outdoors which, he believes, is the first step: ‘You can’t be what you can’t see.’ He’s started the Outsider Project initiative, working with several outdoor brands to help shape their response to Black Lives Matter, as well as lobbying institutions and governing bodies, asking what they are doing to promote diversity in the outdoors.

‘The outdoors is amazing,’ he says. ‘But we only know that because we’ve had the pleasure of being involved in it during our lives. We need to ask, how do we give others that access and opportunities, and the confidence to take those first steps into the wonderful outdoors rather than just telling them: “It’s great”?’